Welcome friends and subscribers to the WBF e-zine.

For this issue containes two pieces.

- "Happy New Year 2010" - and a look at where we've been

- "Half Right is Half Wrong" - a significant refinement to the most powerful yet least understood and utilized tool in our writers bag of tricks.

Hope you enjoy this month's selection. For comments and questions you can reach me at Richard@write-better-fiction.com. I'd love to hear from you.

I can only do so much alone - I could use your help.

Help me help your writing friends. Recommend them to this e-zine by sending me their names and email addresses and I'll send them an invitation to receive this free monthly e-zine. No spam - just an invitation. They'll need to opt-in.

In next month's e-zine I'm publishing a short series on the changing state of the publishing industry as well as an article called, "The Book Must Sell Itself" - a must read for anyone considering self-publishing.

Happy New Year!

2010 has finally arrived.

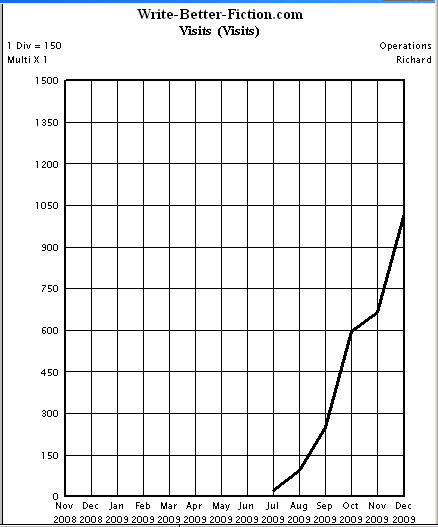

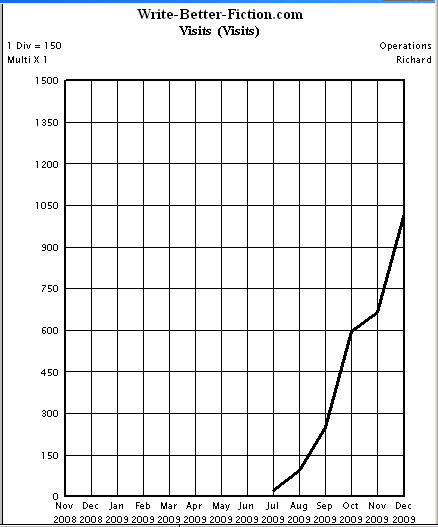

I don’t know about you but it is with some relief that I acknowledge the passing of the "holidays" and look forward to getting on with this New Year. First, I want to welcome a number of new subscribers, and congratulate you for taking action to increase your knowledge of this slippery craft we call writing but which would be better called "storytelling". And most importantly thank all of you for your continued support. www.write-better-fiction.com came into existence on July 25, 2009, when it posted its home page for all the world to see. This site was created because of my desire to help aspiring writers (storytellers) so that they might achieve their dreams without wasting countless years (like I did) wandering through the maze of false and misleading data that passes for information on the subject of writing effective fiction. In the first 30 days I learned enough about websites and everything that goes with them to put up the first pages and then I started blogging and barely two months ago I put out the first newsletter or e-zine. All of which is thanks to you, my friends and fans who have encouraged, ask questions and validated the information that I've made available. This is a hearty "Thank You!" to each and every one of you for your tremendous support. For without you to talk to, it would be very hard to stir up the motivation to continuously confront this most aberated and confusing subject of fiction and codify it into the simple, understandable subject that it should be. By way of validating your support I'd like to share what you have helped create and the effect we are having on aspiring writers all over the world. Although there are still over 280 articles containing 1,700 pages un-posted and unpublished regarding the technology of writing effective fiction, www.write-better-fiction.com has received 2,662 visits and 5,471 page views since day one. And this is mostly thanks to you for telling your friends and helping spread the word. We are helping fiction writers from 32 countries acquire the tools and understandings of the craft to Write Better Fiction which is the first step of selling more of their work. Of course, we still have a little way to go to make the world safe for fiction writers but the monthly graph looks like this:

And there are very exciting things planned for 2010 which all of you will be part of. The first e-book will be available around the end of January and a second e-book a couple months after that.

The first Teleseminar is in the planning stages, with a live seminar to follow a couple months after. And I have a couple of big books outlined plus a comprehensive Dictionary for Fiction Writers. This Dictionary will contain the correct definitions for lots of words specific to writing fiction that have been clearly codified and reformulate so that we can think with these terms and use them. A technology is only as good as its nomenclature is well defined and workable. Unfortunately, the technology of writing effective fiction was all but erased by pompous academics that have so twisted our nomenclature as to make the subject incomprehensible, un-learnable and therefore all but impossible to do anything with. Some may think I exaggerate. But I assure you this is an understatement. One only has to consider the 80% failure rate of the book publishing and movie business (the two industries charged with selling and distributing "stories") and realize that these businesses are manned by the graduates of academia; to realize that something must be wrong with what they've been taught behind those ivy-covered walls. No, I make no exaggeration when I say that the nomenclature of storytelling was so screwed up that it took ten years to reformulate it into a workable codification of terms and definitions that any aspiring writer of normal intelligence could actually think with and work with. But that work is almost done - and we storytellers will have a Dictionary that we can actually use to understand what it is we are doing and how to do it. And just in case you are tempted to think that you already "know all about it"; compare the definition of the word "story" below with what you find in 10 different dictionaries and then you'll see why we don’t have a nation of Hemingway s. Now, enough preaching to the choir -- you guys are already here. You already know that there is something to know. Please continue spreading the word, and let's see how fast we can save other aspiring writers from a fate worse than death - giving up as writers.

Something Special

Next I have something very special for you. This month's article concerns a discovery about the second most important concept in the field of storytelling, second only to the correct definition of story itself. Even a slight shift in the understanding and application of this datum should have an effect on every other datum that you think and work with as a writer. And what I'm revealing is not a slight but a fundamental clarification. Please, take a moment and write me when you finish this article.

Whether you agree or disagree, your feedback will help me greatly in selecting content for forthcoming newsletters.

Sincerely,

Richard A McCullough

Half Right is Half Wrong

The largest single issue for fiction writers is not "how to write" but "what to write" - what to have happen next, and next, and next....

We are not plagued by a lack of imagination but by the very abundance of imagination. There are too many possibilities, too many possible directions, courses, actions, etc., that we can choose for our characters to take.

Our imaginations do not fail us because they are empty but because they overflow constantly with a multiplicity of possibilities. The problem then is not lack of choices but too many of them. The question then is how do we choose?

Some of us rely on the "muse" or instinct. We arbitrarily pick something because it "feels right" and press on hoping for the best, trusting to our intuition.

And if we are lucky, more of the pieces fit together than not and the magic sort of works - mostly - and we manage somehow to get to the end of the manuscript.

But there is a better, surer way of managing this multiplicity of choices that any story idea presents, and continues to present right through to the end. There is a little understood and all too frequently underutilized tool for making these choices. This tool when properly understood and utilized vastly improves the odds of not only finishing the manuscript but ensuring that it's a good salable story. A story that people will want to read and having read will feel that it was worth the effort.

You see, all the sound and furry we can pore into our story will not compensate for the lack of having something worth saying to the audience. And all the incantations to the muse will not yield the simple assurance of "what to write" as when we use the right tools.

But our single most important and most powerful story creation tool was flawed, and hence inadequately understood and so, underutilized.

This tool is the all important "premise".

A well formed and simply stated premise provides the spine upon which all other story elements depend and are connected. It is the backbone that supports the skeleton upon which are attached the mussels which support the organs, tissues and nerves, etc., etc…

However, a novel is not just one story and therefore not designed based on just one single premise. God bless Egri for his invaluable work on "premise", but he only got it half right, and half right, is half wrong. While Lajos Egri's book The Art of Dramatic Writing is a watershed in the field of writing effective fiction, he stopped short of actually discovering the most important aspect of the relationship between "story" and "premise". A novel, movie or even a short story, is not composed of only a single storyline, but several. And therefore the novel or short story is not composed of only a single premise, but several. Any story must illustrate two or more premises, not just one.

Consider carefully the ramifications of the above statement. If bells aren’t going off in your head like the Vatican at Christmas - then you better check your pulse. Because if you have ever written, or even attempted to write a story, you've fought with this invisible conundrum. But like a ghost it has evaded detection, let alone solution. Until now. This is, without a doubt, the second largest and most significant datum in the field of writing effective fiction. Second only to the correct definition of the word "story" itself. Lacking this important fact one could go mad trying to deconstruct a novel to find its premise and therefore become disillusioned as to the validity of Egri's work. Or even more importantly in trying to use a premise to construct a story.

Why is the premise so important? It is the very spine from which every major movement and minor detail of your story is formulated and connected.

If you don’t have a well formulated premise you'll have a very hard time constructing a good, salable story.

And if your audience doesn't agree with your premise they'll have a very hard time liking your story.

Egri was right about the necessity for a premise in good fiction however, he only had it half right. Egri thought that a story only had ONE premise when in fact even the simplest story must have at least two. Larger, more complex works, can easily (actually must have) a number of premises - which I'll get into in a moment. This omitted fact evaded me for years. Its discovery also sheds a different light on a point regarding the very core of what a story actually is, what it does and how it goes about performing its magic. The character conflict is only a function of the conflict of premises.

Consider the definition of story: (note: For those of you who may not be aware - the following definition of "story" will not be found in any dictionary but had to be reconstructed from the derivations of not only the word story itself but the derivations of a hundred other words relating to the art and craft of storytelling.) Definition: Story - a narration, consisting of an introduction leading either to an event (or two causally related incidents, culminating in an event) and ending with a conclusion of the premise of the narration.

Usage Note: The two basic story structures are: the "short story" consisting of an introduction, event and a conclusion, and the "long story" (such as a novel, play or feature film) consisting of an introduction, first incident, second incident, event, and conclusion. These two structures are also referred to respectively as "One Act" and "Three Act" stories however, it can be seen that the One Act story consist of three, and the Three Act story consists of five major components.

Of Further Note:

The one act story if scaled down to its bare minimum in terms of words while ramping up the color of the language at some point becomes what we refer to as a "poem". However it should be understood that poetry is not a subject unto itself but rather a style of storytelling and is best understood as one end of the gradient scale with prose on the other.

Hence we have poetic and prosaic as merely points on opposite ends of the spectrum of narrative style: Poetic <--------------------------------------------> Prosaic While the above is absolutely correct it leaves out one very important point. To have any story at all there must be some form of conflict. For without conflict there would be no incidents leading up to an event (in the case of the long format novel) or no event (in the case of the short story). The key to understanding this concept lies in understanding what constitutes an "event". So, the concept of "event" warrants a closer look here. The "event" is where these two conflicting premises collide and one prevails.

What is an "Event"?

While it is true that an event is something that happens which contains duration, significance, and finality - that definition leaves out something very important. Events, for our purposes as storytellers, must also involve people. Or animals, plants, or inanimate objects that have been ascribed human qualities. And an event, to be an event, must contain a struggle for an objective. Why the necessity for struggle? Because there must be, not only an objective, but one or more barriers to achieving that objective. Otherwise - boy wants girl, boy gets girl - the end. That's about as boring as watching paint dry. And boring is one thing that no audience will ever put up with. (I discuss this in detail in another article about what the audience is actually "buying".) The hint to this important fact was contained in the element of "significance" which implies that this thing that happened had a level of importance to the participant; however, I never took the next step and determined why it would be important. But when we ask "why?" the element of conflict drops into our lap. An event has significance precisely because, and only because, the character involved is attempting to achieve, or acquire something whose acquisition is important or significant to him and he is barred from that acquisition. If there is no barrier, there is no conflict, no event and hence, no story. The protagonist doesn't have this thing, but wants it (better still he "must have it"). And there is a possibility that our character might fail in achieving this all important objective. This is all part of the "significance" package. The struggle is significant but only because the outcome is significant. The protagonist must achieve the objective but can't because some barrier or barriers are stopping him. This "goal" and the attempt, necessity and difficulty in achieving it, is the core of the conflict and therefore what makes the outcome an "event". The Event is the exact point where the character achieves or fails to achieve the objective. The "conclusion" of the premise and therefore the conclusion of the story, runs from that point of success or failure to where we type "the end". Therefore, we have one storyline for the protagonist who needs to achieve the objective, and his struggle leading up to the event, wherein he succeeds or fails. And at the same time we have another story line for the antagonist who needs to achieve the same or a conflicting objective (to the protagonist) and his struggle leading up to the event wherein he succeeds or fails.

Thus, keeping it as simple as possible for purposes of illustration, there must be at least TWO character lines in conflict to constitute a story.

And each story line must illustrate a point, which we call a premise.

It's not enough to simply have to characters slugging it out. There must be two premises, two ideas, slugging it out. The protagonist and the antagonist are each illustrating two different premises. It's the premises that are in conflict. The characters illustrate these premises.

Characters who illustrate no premise are cardboard cutouts no matter how many moles, dimples, or character flaws we hang on them. Unless their actions are informed by a premise they will never "come to life". Premise is that bolt of life force that makes Frankenstein get up off the slab and walk around. Without a premise we will never have more than a collection of body parts stapled together.

It is the premise that dictates each story line. And collectively these different character lines form one story. But the one story itself does not necessarily have just one premise, which is the main point here.

Because the path of each of the main characters is illustrating a different (but related) premise. Now, theoretically the conflict between the two or more main characters could collectively illustrate one premise - but this is not necessary. The overall point of the narrative could simply be that these two ideas are in conflict.

Summary:

Premise is so central to the very nature of a story that it affects every aspect of storytelling. Hence even a small shift (and the above is not a small shift) in this fundamental concept should cause a far reaching ripple effect influencing all other principles of storycraft (which it does).

Let's consider just a few of the many story elements affected by this refinement in the concept of premise.

- Any story (novel, short story or movie) is composed of one or more characters whose objectives are in conflict.

- Conflict consists of an objective that must be achieved and the barriers to that achievement.

Which refines to "two or more premises that are in conflict".

We would think that the two points above are so well know that they would never be violated yet more than half of the movies and two of the books I reviewed last month failed miserably on both counts.

- The character conflict can be direct or indirect, internal or external to any one of the characters. Meaning it could be internal and indirect for one and external and direct for another. There are numerous (almost unlimited) combinations. The numbers are limited only by the sheer number of characters and possible relationships.

This is a new point regarding the relationship between story structure and the story lines of each of the characters.

- Each of the main characters' paths, in attempting to overcome the opposition to their goals, illustrates its own premise.

This is new data and of significant importance in story design.

- Collectively these premises could add up to illustrating a separate additional premise or simply illustrate that these ideas are in opposition to one another.

This is new data and of significant importance in story design.

- A story only has one event but must have two or more "premises". Each premise is illustrated through the actions of a character. It is these premises that are in conflict. And the "Event" of the story is the culmination of that conflict.

This is a point of basic story structure. The stories mentioned above failed because they lacked a premise and therefore a conclusion. As such, despite all the drama, action and explosions they failed to communicate anything to the audience, and therefore failed in their function as stories.

- Basic story structure consists of: the introduction where the characters, conflict, and premises, etc. are "introduced", the event where the conflict is resolved and the conclusion where the premises are concluded.

This is new and important. I've found no other books on writing that identify the five parts of a long format story let alone explain the function of the introduction and conclusion.

- Each main character illustrates his or her own premise. That illustration is the storyline for that character.

- The conflict inherent to any story is not character conflict but premise conflict. For the characters only illustrate the conflicting premises that form the skeleton of the story.

This is new and important data. Egri's book is the only one that I've found that talks about the necessity of a premise for a story but it's only half right.

- Only by working from a collection of premises can a story be designed before the author attempts to compose it. And only by working from such a design can the composition be swift and sure, thus eliminating countless hours of repair known as re-writing.

- Only by executing a good designed can the author craft a story with assurance that it will be well received by the buying public.

This is new and very important data. Although countless writing books talk about the importance of the opening of the story none mention the necessity of including the premise in that opening and none of the books explain the relationship of the premise to the conclusion. And the conclusion is where the reader gets the payoff for the time and energy they have invested in reading your story. Therefore, the premises, and how they are illustrated and your conclusions of them, are the major determining factors in the ultimate success or failure of your story.

And now we know that we must have, not one or even two premises for our story, but one for each main character. This should be a major help in figuring out "what" to write.

And understanding "what to write" is fare more important, challenging, and financially rewarding than "how", any day.

Write on....

Richard A McCullough

P.S. You can write me any time. Your questions and comments are always welcome.

New! CommentsHave your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.

|